Editor’s Note: Please see Annuities Part I here.

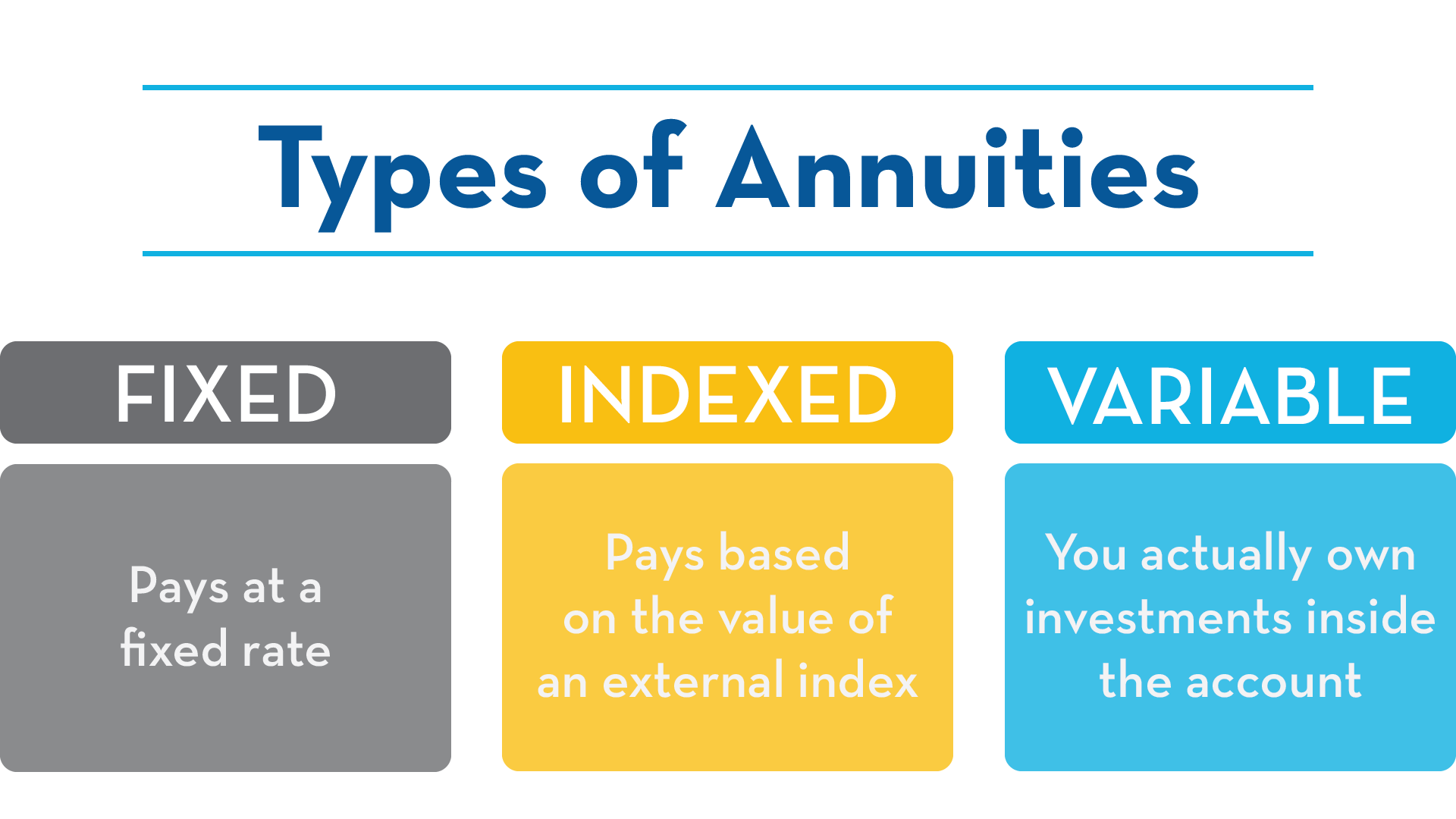

Another reason I don’t like fixed rate, fixed index, and variable annuities is their low returns and high costs. These are directly related. The higher the costs to you, the lower your returns.

To begin with the simplest of the three types, fixed rate annuities are the exception in that they do not charge high fees. In fact, generally they don’t charge you any fees at all. Instead, they offer you very low returns.

I recently pulled some quotes from my preferred insurance company. For amounts less than $100,000 I could earn 2.6% guaranteed on a fixed rate annuity for the next five years, and I could earn 3% if I invested more than $100,000. I checked rates with another provider online and received quotes in the similar range of 2.8% and 2.95% respectively. That rate changes over five years. Mine had a minimum reset rate of 1.3%, after the five year term.

What should we think about these rates?

With a product like this, you should always reasonably expect that the annual return on a fixed rate annuity, adjusted for inflation and taxes, will be approximately zero. That’s not a typo. That’s just a rule of fixed rate annuity products and risk-less products in general.

Now, figuring the returns of fixed index and variables annuities is trickier because they are somewhat market driven and depend on what you pick as underlying investments and risks. But we can understand what the costs are, and therefore their expected underperformance versus comparable assets you could buy from a brokerage company.

With a variable annuity you have the chance to purchase mutual funds similar to funds at a brokerage account. Costs will weigh down your returns, however.

The management fees of mutual funds offered inside a typical variable annuity are typically very high. In the 2018 Brighthouse Financial Life (formerly MetLife) policy variable annuity contract I reviewed, the costs of mutual funds ranged from a low of 1.56% to a high of 2.71%. Hello? 1987 just called, and it wants its mutual fund fees back.

The cheapest 1.56% fund was a stock index fund which low-cost brokerages offer at 0.05% – or 31 times cheaper elsewhere. I really didn’t enjoy the 1.66% fees quoted on the Blackrock Ultra Short Bond Portfolio. That fund has a 10 year return of 0.39% – meaning you could have locked in huge losses after fees for the past decade, on a product supposedly meant to preserve capital. These types of egregious fund management costs are the rule, not the exception, when it comes to most variable annuity fund offerings I’ve reviewed. The Teacher’s retirement System (TRS) in Texas just capped mutual fund fees inside variable annuities at 1.75% following a “reform” in October 2017, to go into effect in October 2019. These fees are, in a word, bad. Even after that “reform.”

Why are the fees so high? I have a theory, and it goes something like this.

Insurance companies can impose huge fees on variable and fixed index annuities because they have selected their customers very carefully. Only people who don’t know what they are doing would select these providers and these products. So in essence they can charge whatever they like.

They employ psychology similar to how the “Nigerian Prince” scam artist who supposedly wants to wire you $10 million will purposefully misspell words in the solicitation email. The Nigerian Prince scammer knows that any target victim who replies has no powers of discernment. The misspelling in the email is a purposeful selection process by which the scammer chooses the right kind of victim.

Similarly, whenever a public school employee sets up a “finance and retirement discussion” meeting with a commissioned insurance salesperson, the salesperson can have high confidence that the teacher has absolutely no idea what they are doing financially. The result: high fees, with impunity!

Of course, there are more fees after that.

Arguably the main service an insurance company provides with variable and fixed index annuities is a lifetime guarantee of payments, because they employ actuarial math that helps them make educated guesses about how long you’ll live. That seems like a service. And the insurance company seems to be taking a risk on you.

Ah, but they aren’t, not really. These complex annuities also charge a fee on your account called the “mortality and expense risk charge” – offloading that specific risk that you live too long – to you.

The 2018 Brighthouse contract I reviewed charged 1.2% per year for this “mortality and expense risk,” and the industry range is an extra 0.4 to 1.75% per year on these products. The lesson: If you charge high enough fees, you don’t end up taking a risk.

Finally, here’s my least favorite of all the low-return/high cost features of fixed index annuities.

This gets a bit technical, but bear with me, because this is really how the sausage is made.

The insurance company calculates the ‘growth’ in your fixed index account value based on the change in value of a stock market index over a year, but does not take into account dividends or the reinvestment of dividends that you would get, were you invested in the market directly through a brokerage account.

Over long periods of time working towards retirement – I’m talking about decades – the growth of your investment may be in substantial part due to dividends. Because of the way the company calculates returns, however, you probably don’t get the return on dividends from a fixed index annuity.

Does this matter? Oh yes.

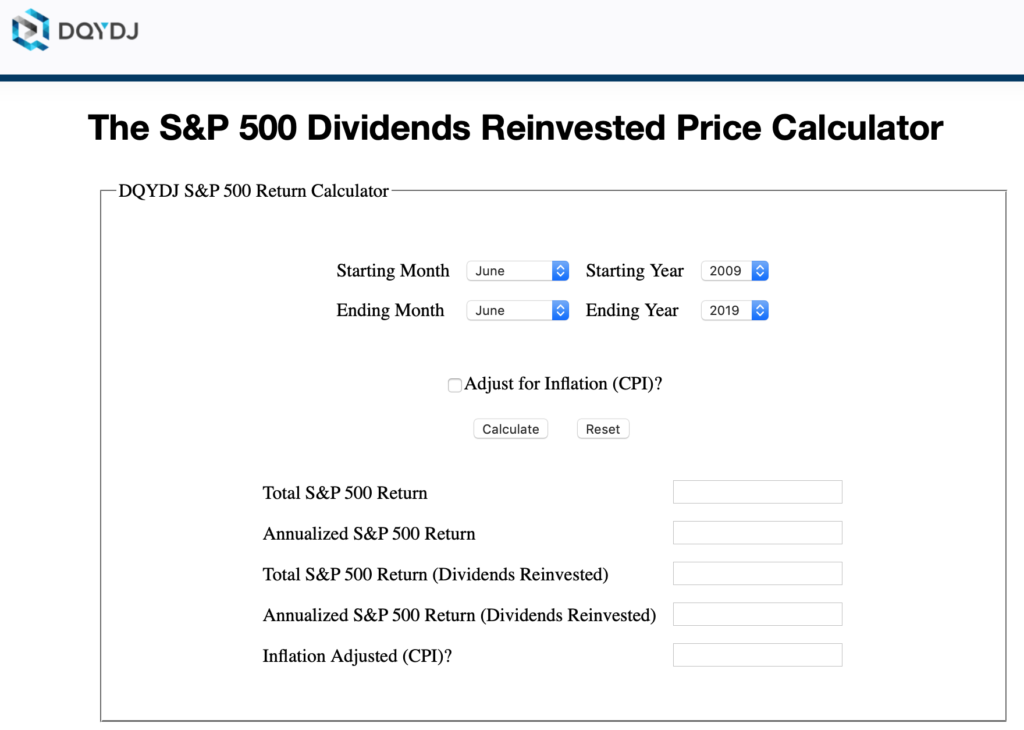

Let’s say you had $100,000 in an S&P 500 brokerage account beginning in May 1989, held until May 2019. The return on the index over 30 years, considering only index price changes, is 7.7%.

However, the return on the index over 30 years, including the reinvestment of dividends, is 9.9%.

Hmm. Is that annual 2.2% difference a big deal? Yes it is. It’s the difference between ending up 30 years later with $818,000 or $1.6 million. But if you, as a fixed index annuity investor don’t get the credit for dividends or the reinvestment of dividends, who kept that money? Do I have to spell this out for you?

Over a long period of time, you may be leaving half your investment gains with the insurance company.

When you are a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Similarly, when you are an insurance company or commissioned insurance salesman, the investment solution everyone needs for retirement is an annuity. It’s what you sell.

As I do not sell annuities, all I can say is: Don’t buy these.

A version of this rant ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

Annuities Rant Part I – The Complexity

Annuities Rant Part III – Condoning in Some Ways

Post read (691) times.