Industrial recyclers of household products such as paper, plastics, metal and glass are having a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year.

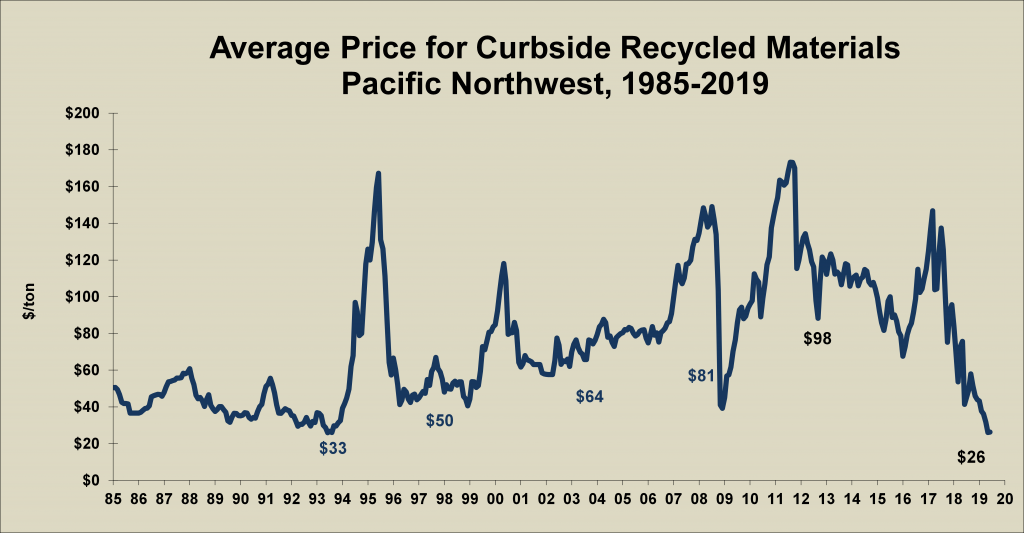

Typically they get paid by cities to haul and process recyclable waste. But they also earn money from selling valuable commodities they extract from this household waste to industrial users. These commodity markets are in a slump.

A China policy change announced in 2017 – called the “National Sword” – banned a number of types of recyclables from importation. Mixed, and otherwise difficult-to-recycle paper, plastics and metals which US recyclers previously shipped across the Pacific Ocean nearly ceased, by 2019 dropping to about 1% of their previous volume. Without an easy market to sell to, parts of the US commodity markets have been in price free-fall, a period of re-adjustment, or just broken.

The effect of this slump for secondary commodity market is both financial and environmental.

Although much of the reporting on the China ban has focused on plastics, the biggest effect financially for the nation’s second largest recycler Republic Services has been on paper products, according to Peter Keller, Vice President of Recycling Markets for Republic.

Paper makes up 75% by volume of what Republic receives from household bins and traditionally sells to wholesalers. Partly because of China’s changes and other factors, this market has tanked in the past two years.

Recycled cardboard used to sell for $200 per ton but now goes for $30 per ton. In addition, households now recycle small cardboard boxes from Amazon, which many recyclers are ill equipped to process, compared to the flow of larger cardboard from retail stores just ten years ago. They recover less, and get paid less, for cardboard than in the past.

“Mixed paper,” a catch-all product that used to sell for $110 per ton in 2017 now costs negative $5 per ton. In other words, a recycler like Republic has to pay a wholesaler to take the tons off mixed paper they process off their hands. What used to be a source of profit is now a source of loss.

Interestingly, a third paper product used to be newsprint. With the national decline of the newspaper business, demand for newsprint has dried up. Your soon-to-be recycled newspaper – perhaps the paper you’re reading from now – now goes into the “mixed paper” stream, with limited-to-negative monetary value today.

I puzzled for a while over how to make a grim metaphor combining the challenges facing the newspaper industry, something about training your new puppy as the best secondary use of my newspaper columns, and overlaying that with the declining value of newsprint as a commodity. I couldn’t manage to make it funny though, so let’s move on.

Secondary metal continues to be a solid B+ student of an otherwise failing recycling class. Bundles of clean soup cans that contain steel command secondary prices like $120 per ton, down from $150 per ton a few years ago. Bundles of clean soda cans that contain aluminum command secondary prices like $1,050 per ton, down from $1,400 per ton in 2017. At these still-relatively high prices, even though soup and beverage cans do not make up the majority of your recycling bin, they can be a significant driver of the overall profitability of a recycling program.

Finally, there’s glass. For a long time now, glass has been the class trouble-maker of the four materials in a recycling bin. While glass is somewhat infinitely recyclable, producing new glass from scratch (well, sand) is generally cheaper than using recycled glass materials.

From a commodity-markets perspective, it is puzzling then that the City of Houston reintroduced curbside glass recycling after a three-year hiatus, to some fanfare, in the beginning of 2019.

Glass that comes through a traditional curbside bin has a negative value of $10 per ton, according to Keller.

Secondary glass is only financially viable as a recycled commodity when sorted carefully by color and somehow cheaply transported to a nearby glass manufacturer, if one exists. According to Keller, if the glass could be cleaned, color-sorted, and delivered to a manufacturer, it could fetch as much as $100/ton. But getting to that result costs too much money.

When glass comes in mixed from a household bin, by contrast, it’s not saleable for a profit, it costs a lot to move because of its weight, and it often contaminates other recycled materials. Think paper products with tiny glass shards. Now how much would you pay? So it’s a loss maker.

Sarah Mason, the Division Manager for Recycling at Houston’s Solid Waste Management Department, defended Houston’s decision to reintroduce glass to me, saying the City’s new recycling partner has custom-built its facility to handle glass more efficiently, hopefully reducing the contamination problem.

And then there’s plastics, which have garnered 95% of the headlines but which constitute about 7% of Republic’s revenue stream.

Even after the China policy change, three types of plastic still have a viable wholesale commodity market, and these markets track the plastic number you’ll find marked on your household plastics. In brief, numbers 1, 2, and 5 still command decent prices as long as they can be separated and processed cleanly. Plastic #1 – your basic single-use water bottle, can be sold for $250 per ton now, down from about $325 a few years ago. Plastic #5 – consisting of heavier plastics – has stayed steady at $150 per ton, while plastic #2 made up of milk jugs and detergent bottles is actually up slightly in some markets.

Other plastic numbers are virtually un-saleable at any price as a secondary commodity following China’s policy change, and will go to a landfill.

All of these prices should be understood as varying geographically as well as varying by purity. A recycling processor that can produce a homogenous ton of product will command high prices, while a mixed or contaminated product will sell for less, if it will sell at all.

Everyone I’ve spoken to in recent weeks expresses the hope that as technology and markets change, some of the broken parts of the recycling market can improve and heal. New and better sorting technology at the recycling processing plant can turn previous trash into viable secondary commodities, although it may take a combination of capital investments, time, and improved engineering to get there.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Recycling Commodity Market Slump Part I – The China Ban

Recycling Commodity Market Slump Part III – The Price of Commodities (upcoming)

Recycling Commodity Market Part IV – What is a Household to do? (upcoming)

Organic Recycling in my city – My new obsession

Post read (602) times.