This is a long post about how Trump has specifically threatened to cause an economic or financial crises through either a trade war or through undermining the US monetary system and credit.

This is a long post about how Trump has specifically threatened to cause an economic or financial crises through either a trade war or through undermining the US monetary system and credit.

[Previous Trump posts in this series introduce my fever dreams of a Trump Presidency, my review of recently-elected authoritarians, and the Machiavellian use his administration could make of a security crises.]

Economic Crisis

Similar to a security crisis, I can’t sleep because I worry Trump may inadvertently cause an economic crisis, which he may then uses as a pretext for further authoritarian moves.

Look, this can’t be a prediction about “what’s going to happen” with the economy under Trump. Most of the time when we talk about markets responding to a presidency, we are finding false signals in noise or we’re predicting things that are really unknowable.

I do worry, however, about two specific economic problems that Trump has promised to cause: Trade wars, and interference with US financial strength through the bond markets and Federal Reserve. The long-term problem with an economic crisis – besides the obvious pain and suffering – is a societal desperation that allows an authoritarian to make bold moves otherwise unavailable to him.

Let’s start with trade.

In the arena of international trade, Trump’s “plans” – such as they are – could and would cause a worldwide trade-war and global recession. He launched his presidential campaign pledging massive 35% tariffs on our major trading partner Mexico. He reiterated his plans many times on the campaign trail to retaliate both against Mexico, and against companies like Ford Motor that may move manufacturing jobs to Mexico. By the way, 16% of our national exports go to Mexico.

In addition, he has threatened 45% tariffs on Chinese exports both in Republican debates and in interviews with the New York Times. Some of our biggest global brands like Starbucks, Boeing, and Apple see the 1.3 billion Chinese people as their largest single market. By the way, 7% of our exports currently go to China.

Trump pledged to withdraw not only from the recently-negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership but also to renegotiate or withdraw from 1994’s North American Free Trade Agreement with major trading partners Canada and Mexico. By the way, 19% percent of all U.S. exports go to Canada.

Trump’s promises mark a very big shift in US policy and leadership.

The problem with unilateral trade sanctions like this is:

- They don’t stay unilateral. Countries affected will obviously retaliate against us with their own trade sanctions, and;

- The United States would probably be in violation of international trade systems like the WTO.

Most experts agree that the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs of 1930 exacerbated the Great Depression worldwide, as both imports and exports from and to the United States dropped to about half previous levels.

The globalization of trade since the end of World War II – and in particular since the end of the Cold War – has greatly favored the United States, even if the effects of trade hurt particular industries or geographies. A reversal of that trade situation – championed by Trump as he champions those most hurt by globalization – will make us all poorer.

At the same time, high tariffs are unlikely to bring back manufacturing jobs. The bad news[1] is that we pay people too much in this country and we enforce too many worker protections to make many manufacturing jobs viable here.

At the same time, high tariffs are unlikely to bring back manufacturing jobs. The bad news[1] is that we pay people too much in this country and we enforce too many worker protections to make many manufacturing jobs viable here.

Trump has promised a trade war, but without a chance that it could possibly “work” in the sense of bringing back many jobs for those most affected by globalization.

Now, maybe Trump is just kidding about his trade war plans. Maybe its just a goof, indicating his direction of thought, but he won’t enact anything as crazy as what he’s promised?

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross

His selection of billionaire investor Wilbur Ross for Commerce Secretary, however, indicates Trump’s seriousness about protective tariffs. Ross made his career as an extraordinarily successful vulture investor in beaten-down industries such as steel and coal, domestic industries buffeted in part by regulations and high worker-costs, but also by international trade.

In 2002 and 2003, Ross bought up bankrupt steel-producers LTV Corporation, Acme Metals and Bethlehem Steel.

A well-timed 30% tariff on imported steel in 2002 enacted during the George W. Bush Administration helped raise the value of Ross’ steel holdings, which he eventually sold to Indian-owned Mittal Corp in 2005.

Ross has indicated his support for both Trump and the idea of protective tariffs, and he clearly has the business experience to know that trade protection can enrich the owners of certain industries.

While higher steel prices help steel workers and owners, however, they hurt other industrial companies – like the auto or construction industries – that need to buy steel at the lowest price possible.

Trade wars can benefit some select sectors and people even while most of us end up poorer through higher costs. International trade has been a major generator of wealth since the end of World War II, with the United States as its biggest cheerleader. I’m afraid Trump intends to kill the golden goose, with severe economic consequences.

Undermining financial strength

The second economic crisis threatened by Trump is his promise to weaken the Federal Reserve. It will take some wise financial counseling to explain to Trump why his threats do not really help the United States. He has not shown evidence, however, that he can take that kind of advice, or learn from it.

I worry that over the next two years Trump will have the ability to reshape the Federal Reserve in ways that undermine one of the central bank’s key strengths – its independence from politics.

The Fed is the quasi-public, semi-mysterious, massively-powerful, independent central bank for the United States. It’s an “independent” regulator, meaning it technically doesn’t report to Congress or the U.S. president. Given its mystery and importance, critics on the Left and Right often seek to curb the power of the Fed. Anything that powerful must be part of some kind of conspiracy, right?

President-Elect Trump — who served as human fly-paper for the bad economic ideas of fringy cranks throughout his campaign — caught this wave too. He accused the Fed of being in the tank for the Obama administration. Like the Republican Party, the Democratic Party, the FBI, the Electoral College, and the media to name a few — the Fed — Trump complained, was part of an unfair conspiracy against him.

But then Trump went further down an even darker path in attacking the Fed. In “Donald Trump’s Argument For America,” released in the days before the election, he linked images of Fed Chair Janet Yellen to the well-known faces of financiers George Soros and Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein, as part of a “global elite” conspiring against ordinary Americans. All three are Jewish, of course, and the ad recalled anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that follow the vile and fictional “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Whether Trump claims that Yellen is in the tank for his opponents, or whether he winks knowingly at anti-Semites about a global Jewish conspiracy, he has set the stage to justify curbing the Fed’s independence.

This video:

This should trouble us tremendously. The U.S. is a country that — despite the confounding popularity of the Kardashians — retains an outsized role in the global economy. One of America’s greatest strengths as a financial power is the belief that its central bank is not unduly subject to political control from any particular party or faction.

Usually when we talk about policies from the Fed, we don’t focus on Democrats and Republicans or Liberals and Conservatives, but rather “Hawks” and “Doves.”

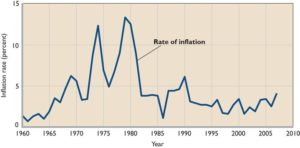

In simplest terms, a “hawk” tends to worry about inflation more than unemployment, and pushes the board to raise interest rates quickly enough to avoid unexpected inflation. A “dove,” conversely, worries more about unemployment than inflation, and would tend to want to keep interest rates low as long as possible, to juice economic activity even if it spurs a little bit of inflation. I’m simplifying here, but these are the broad strokes.

A key point, though, is that a Fed governor — whether hawk or dove — is supposed act independently from politics. Almost as important is the idea that a Fed governor seems to act independently from politics. We count on the appearance of independence as much as the reality.

The first guarantee of independence is that the seven board members, known as governors, serve 14-year terms, thus guaranteed to outlast any U.S. President. A bit like justices appointed to the Supreme Court for life, Fed governors therefore should not owe their ongoing positions to any particular political faction. The next guarantee of central bank independence is that the Fed Chair is nominated by the President from among the governors and gets appointed to a four-year term that does not coincide with a President’s four-year term. Janet Yellen, the current Fed Chair, plans to stay in office at least through her term in 2018.

The specter of political interference in Fed policy has darkened our political scene before. Economist and former Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota recently wrote about historical problems when the executive branch interferes with the US Fed. During and following World War II, the Fed kept long-term rates artificially low to allow the government to borrow cheaply. Inflation soared to nearly 10 percent by the time the Korean War began in 1950. Later, Narayana reports, Presidents Johnson and Nixon pressured the Fed to stimulate the economy, leading in part to astronomical inflation of the ’60s and ’70s that peaked at 14 percent in 1980.

With President Trump able to appoint a new Fed chair and vice-chair in 2018, plus the chance to fill two more currently open spots on the Board of Governors, a real point of pressure exists. By 2018, he will have appointed four of seven Fed governors. Would Trump show restraint, or would he pressure the Fed to support his agenda?

Authoritarians, as a rule, cannot stand independent central banks. They don’t like the idea that some entity independent of them can wield vast power over both the real economy and banking institutions.

The U.S. enjoys a massive financial subsidy because, up until now, the wealthy of the world trust that our currency will not be suddenly inflated away to worthlessness. An independent Fed assures the world that authoritarians cannot bend monetary policy to their will. But authoritarian regimes, the kind that curb central bank independence, never get trusted with this kind of financial status, as a place where global holders of capital want to park their surpluses.

There are many areas where Trump’s actions might undermine our strengths as a country. Attacking the independence of the Fed is one of the most important ones to watch out for.

Threatening bond markets

Last but certainly not least, it takes a long time (dating back to Alexander Hamilton!) to build up the kind of credit the United States gets for political independence in monetary policy, as well as the kind of trust that attracts global capital to fund our government. It probably only takes one aggressive authoritarian to make that capital flee. And if it flees quickly, that alone can cause a financial crisis.

During the campaign last Summer, Trump argued that if the US borrowed too much, he would simply re-negotiate our debts.

“I’ve borrowed knowing that you can pay back with discounts. [As President,] I would borrow knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal.”

Um. Wut.

Holy fucking shit. Gah. That’s not how it works with the US bond market. You don’t default (that’s what “making a deal” means) on the US bond market. Or at least, you don’t get to do it more than once. Because suddenly you’re Argentina, or Ecuador, or Ukraine when it comes to your ability to borrow.

He’s talking about treating our country like one of his Atlantic City casinos, walking away and stiffing our lenders. If bond investors took him seriously and literally (like I do) we’d have an immediate financial panic. Personally I think Trump’s attitude towards US sovereign debt is the scariest thing he’s ever said, in terms of a threat to the continuation of the United States of America as we know it.

He’s talking about treating our country like one of his Atlantic City casinos, walking away and stiffing our lenders. If bond investors took him seriously and literally (like I do) we’d have an immediate financial panic. Personally I think Trump’s attitude towards US sovereign debt is the scariest thing he’s ever said, in terms of a threat to the continuation of the United States of America as we know it.

And that’s saying a lot, considering what’s come out of his mouth or Twitter account.

Who will be to blame?

If an economic or financial crisis occurs under a Trump administration, I don’t see the events as something that would cause Trump to reflect on his actions or take responsibility for his errors. I think he will see the crisis he caused as an opportunity to blame his enemies.

Surely it will be fault of the Mexicans, or the Muslims, or the Chinese, or the Jews, or the journalists that his trade war or threats to default on our sovereign debt have hurt markets and the US economy.

An economic crisis – like a security crisis – can make people desperate for action, any action (however rash) to make it better. People who are angry or fearful about losing their jobs or financial status or fortunes are more likely to turn a blind eye to constitutional encroachments.

Those constitutional encroachments are in the end what I’m most worried about, and are what I will write about next.

Parts of this post appeared as two different columns in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Trump Part I – Fever Dreams

Trump Part II – Review of Recent Elected Authoritarians

Trump Part III – The Use of Security Crises

Trump Part V – The Constitutional Crisis

Trump Part VI – Principled Republican Leadership

And related posts:

Candidates Clinton and Trump: Economic Policies

Candidate Trump on US Sovereign Debt

[1] It’s actually good news, but you know what I mean.

Post read (397) times.