Q. Michael, I am trying to understand something here. The government spent a ton of money that it didn’t have stimulating the economy post Covid. This caused inflation to increase. So the Fed boosts its rate to cool inflation. When the Fed boosts its rate, banks have to pay to borrow money from the government. Does that higher rate go back to the government? It’s sort of like a tax on those who don’t have money to pay for houses and cars. So the poorer portion of our society is being taxed to pay for government spending. Those who have funds to pay cash aren’t really affected by the higher rates. Is this logic correct? Thanks, I always read your column.

Alexander McLeod, San Antonio TX

A. My short answer to your final question of “is this logic correct?” is mostly “no.”

But I like your question because it combines the top three drivers of economic news in the past two years – federal debt, inflation, and the Federal Reserve – and asks for logical cause and effect linkages between them, and real-world implications. Understanding how they interact is important. I’ll do my best to break them down, using your question as prompts.

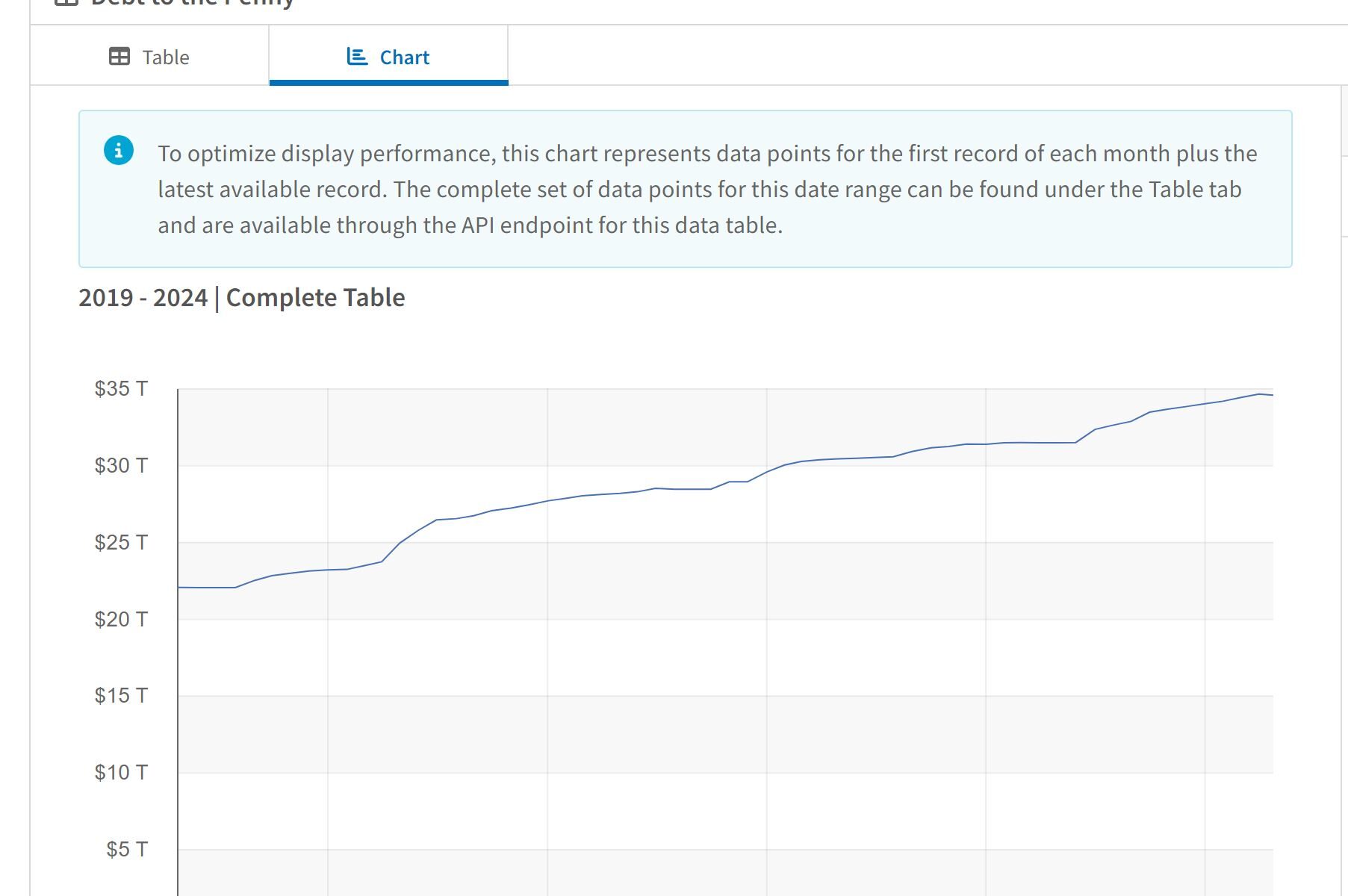

Yes, the government did spend money it didn’t have. That is an ordinary thing for the US and most other governments in the world over the past century. Or basically forever. The magnitude of US borrowing has gotten substantially larger in the past decade. We do not have an actual answer yet for “how much is too much debt?” but the activity itself is highly precedented. Am I worried? Yes. But we don’t have certainty on whether we’ve hit limits or what the limits are.

“This caused inflation to increase” is not the right cause-and-effect. More accurately, the combination of low interest rates, extra fiscal (COVID) stimulus, and an energy shock from the Russian invasion of Ukraine probably caused inflation to spike dramatically in the summer of 2022. The rate of inflation has since dropped to a normal range, even if prices (outside of energy) have not declined. Prices rarely outright decline.

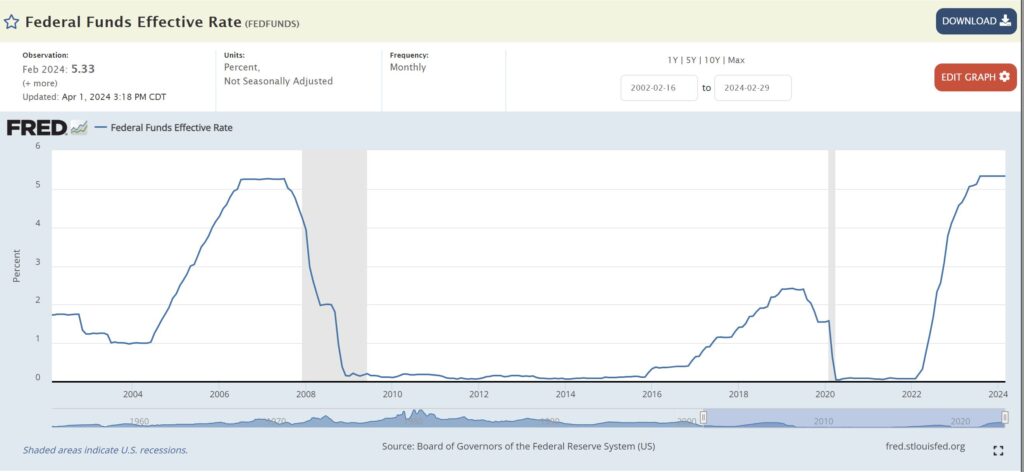

The Fed did boost rates beginning in 2022 to cool inflation, as a 2 percent inflation rate is one of its key goals and mandates. Inflation is around 3.5 percent as of this writing, and the Fed as a result has indicated recently that it may not lower rates until further progress is made on inflation.

Higher benchmark interest rates are set by the Federal Reserve, technically both the country’s central bank and also technically a non-governmental entity. The interest paid and the interest earned by the Federal Reserve requires an extra step of explanation for accuracy.

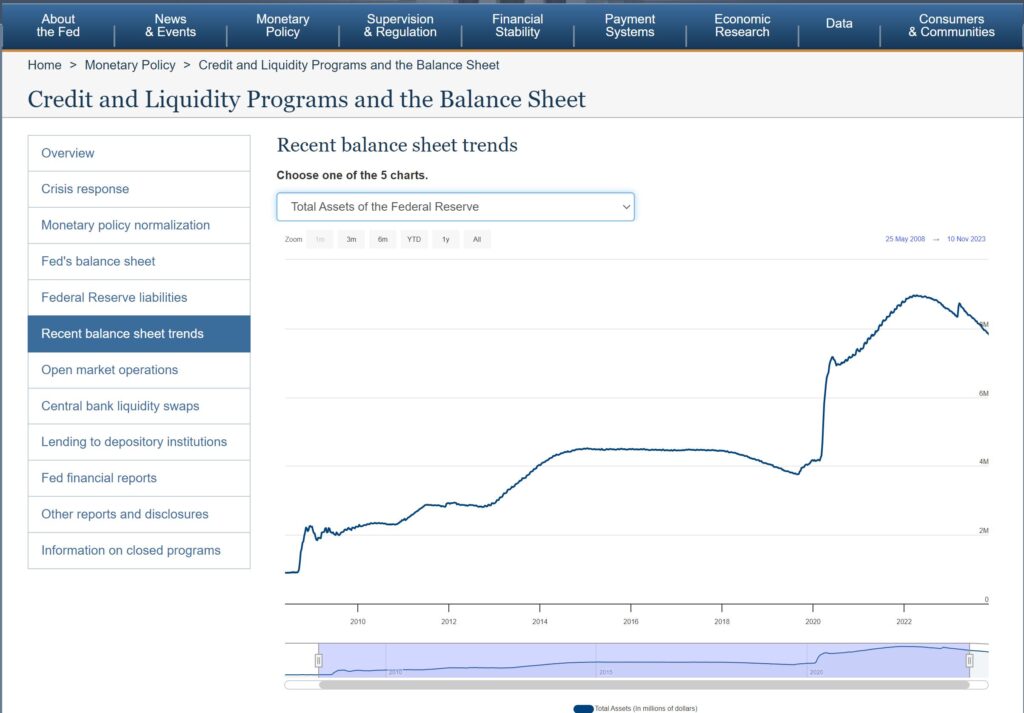

As the central bank for the US, the Federal Reserve actually pays interest to banks for their excess reserves. The Federal Reserve also uses funds to go out in the marketplace to buy US government bonds, and earns interest on the rate that the US government pays on its bonds.

“Who is making extra money off of higher interest rates?” is part of your question, and viewed a certain way, the Federal Reserve actually books extra interest income based on the difference between what it pays banks for deposits and what it earns on securities with its balance sheet.

Private banks, which raise interest rates on consumers and businesses when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates on them, may earn higher interest income in this environment than they did before. But private banks are not the government.

The federal government, by contrast, earns no big amounts of money from higher interest rates.

Not at all. Basically, just the opposite. The US government, as a massive borrower, pays more in terms of higher interest rates.

The Federal Reserve may earn money as a net lender if it chooses to own more bonds, especially following times of monetary stress like 2008 and 2020. Private banks may earn more as lenders in a higher interest rate environment. The federal government, however, pays a lot more.

To your question of whether higher rates are like a tax on people who do not have money to own cars or houses by paying cash for them, I would say “sort of,” but that it’s not very specific to our current higher interest rates environment. What I mean by that is that in every interest rate environment, low or high, individuals who borrow month to month on their credit card are paying in the 12 to 25 percent interest range. That’s the real and substantial tax on people who borrow, but it happens all the time, not just now. And the “tax” goes to banks and credit card lenders, not the government.

Wealthier folks, or people with substantial savings in the bank, are in a position – right now – to earn more on their savings than they have over the previous 2 decades, roughly 2001 to 2022. That’s again neither a tax nor a government bonus, but a private sector cost or benefit of participating in the banking system and earning interest on one’s savings.

Your statement “the poorer section of our society is being taxed to pay for government spending” is an inaccurate understanding. To vastly simplify things, I would generalize the situation the following way instead:

Folks with no savings (generally poorer, but this can include middle- and upper-income people as well) are generally paying high interest rates to credit card lenders in every interest rate environment. At all time.

Folks with middle and upper incomes who borrow to own a car or home are paying higher interest rates, right now, to private lenders on their car and home loans. But again that extra income is captured largely by private lenders, not the government.

Wealthier folks and institutions with surplus funds are earning higher interest rates on their savings and interest-bearing investments. If they lend to the US government by buying government bonds, they are earning a lot more now than they did two years ago.

The federal government is a pauper in this scenario, and is paying out higher interest rates. Not exactly like on a credit card, because the rates are roughly 4.5 to 5.5 percent. But that’s much worse than the 1.5 to 2.5 percent it was able to pay a few years ago. The Federal Reserve pays higher rates of interest for private bank deposits, but also earns higher rates on the bonds it buys. Although it has higher earnings in recent years, that has more to do with its larger post-crisis balance sheet than anything else.

As for “those who pay cash aren’t really affected by higher rates,” I’d say that’s somewhat true. But more than that: those who have cash are benefitted by higher rates, since they can earn more money on their savings.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (63) times.