A very cool story in the October 2024 issue of Texas Monthly hit me personally as a modern version of that memorable moment in the movie The Graduate, like a quiet investing tip given out by the pool during a cocktail party:

Texas Monthly Article: “I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.”

Me: “Yes, sir.”

TMA: “Lithium.”

Me: “Exactly how do you mean?”

TMA: “There’s a great future in Lithium. Think about it. Will you think about it?”

I thought about it.

The Bull Case For Lithium

Oil and gas isn’t going away any time soon, but we are in the early years of rapidly ramping up alternative energy sources, including especially here in Texas.

To get from here to there in the energy transition, we’re on a path to use a lot more lithium, a central ingredient in the lithium-ion battery powering your utility scale batteries for renewable-energy storage, your Tesla, and also your iPhone.

The chart showing demand for lithium is a one-way line, straight up.

A McKinsey study from 2023 expects 27% annual growth of demand for lithium-ion batteries between 2022 and 2030.

The growth of batteries is closely linked to the growing demand for lithium, of which 90 percent is for electric vehicles and battery storage. As a result, the International Energy Association foresees an eight-fold increase in demand for lithium between 2023 and 2040.

The three largest sources of lithium mining are in Australia (33 percent), China (23 percent), and Chile (12 percent.)

The US hasn’t opened a lithium mine since the 1960s, and for a variety of good environmental reasons maybe we shouldn’t. Current techniques may make it impossible to onshore lithium mining to the United States – due to environmental concerns such as water contamination and injury to the landscape.

China currently dominates the lithium-ion battery industry, supplying 80 percent of batteries worldwide. It is also the largest lithium refiner in the world. Average prices for lithium were five times higher in 2022 than 2021.

Texas Monthly article

So, back to the Texas Monthly article, which is excitingly titled “The Lone Star Lithium Boom,” and the story is quite cool as well. A Baylor-trained chemist living in northeastern Texas developed a process – a while ago – for extracting lithium from briny water. He set up a company called International Battery Metals (IBAT) to commercialize his patented process.

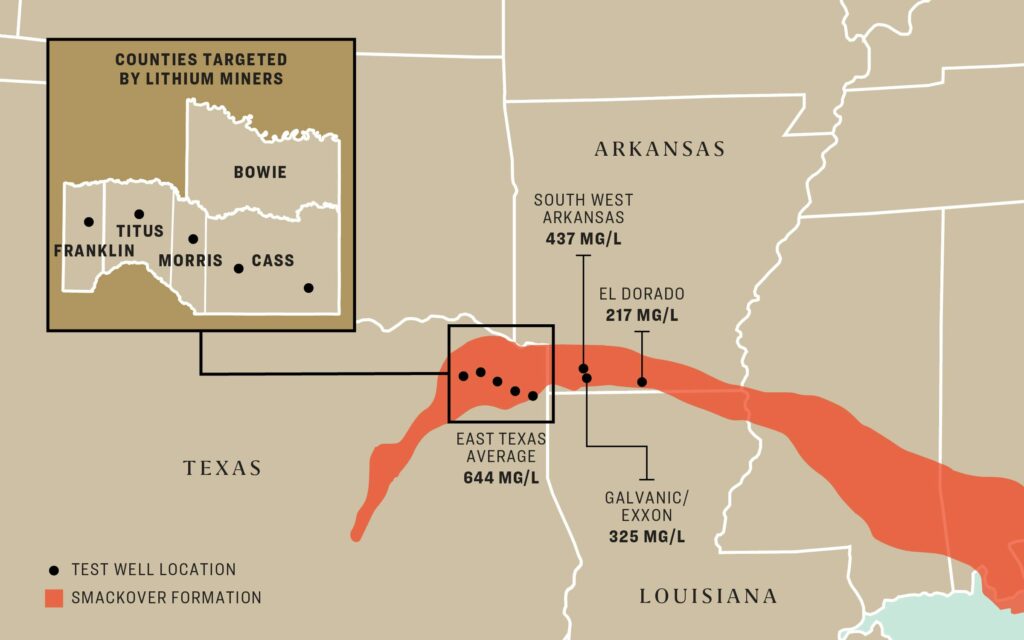

The other weirdly exciting Texas angle is that a large southern swathe of Arkansas and northeastern Texas is unusually rich in the briny water that makes for concentrated lithium extraction using his technique.

According to the article, IBAT recently opened its first commercial lithium-extraction operation in Utah this summer. Meanwhile a Norwegian oil company has partnered with an Arkansas-based company that has a similar lithium extraction method. They are aggressively leasing briny water acreage in East Texas. Reuters reports that Exxon Mobil also has big plans in a section of Arkansas to begin lithium extraction.

Houston-based companies SLB and Occidental, plus Saudi Aramco and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company all have indicated interest in lithium extraction, giving further credence to the large scope of the opportunity. A further hope and claim of lithium-extraction from briny water is that it avoids the high environmental impact of traditional mining.

As a hot tip, Is this a good investment?

In the specific sense of one man’s entrepreneurial quest to invent and perfect a process to respond to a global market opportunity – it’s undoubtedly super risky as a standalone investment. IBAT in particular is a penny-stock company listed on the Canadian Securities Exchange, a situation which always gives me the ick.

On the other hand, you can’t help but cheer for a guy who was super early in developing a process that might respond to a megatrend of the next decade, and has many giant companies looking to get in the game.

Malthus versus reality

My biggest takeaway from this story is renewed optimism. A few years ago a frequent complaint about the energy transition was that the rare metals required to make large-scale batteries and other high-tech hardware were located in dangerous or unfriendly countries, creating a choke point against progress.

But you know what? When the demand gets high enough and prices respond, entrepreneurs get busy finding new ways to solve most any choke point.

In the late 18th Century, economist Thomas Malthus proposed a view – totally wrong as it turns out – that scarcity and increasing shortages of vital goods would be the fate of humanity as our population grew. The Malthusian worldview – proven wrong over and over again – often dominates our expectations for the future.

“Peak Oil” has been declared numerous times since the 1970s. Decelerationists and anti-growth people often adopt a Malthusian mindset – this idea that the world is running precipitously towards a commodities cliff, after which declining living standards will follow scarcity and shortages. Instead, our actual lived experience – decade after decade, century after century – has been one of increasing abundance since Malthus. Abundance not just of food but also fresh water and sources of electricity and all the things that make humanity materially better off generation after generation.

This is the right framing of the lithium story. Step 1: Demand explodes for lithium due to the innovative roll-out of batteries to solve a huge number of human problems in the twenty-first century. Step 2: Prices of lithium rise fivefold in response to the demand. Step 3: Some clever chemistry PhD develops novel extraction techniques. Step 4: If prices get high enough and the technology gets good enough, he could be rewarded handsomely. Step 5: In the meanwhile, others will follow his lead, improve upon the technology, provide massive amounts of capital if the price is right and the need is there, and discover commercially profitable ways to get the thing we need.

Incidentally, after a huge spike in price and demand for lithium in 2022, prices actually dropped 75 percent since the beginning of 2024. Commodity prices are notoriously volatile. As exciting as the future opportunity for lithium is, don’t go investing everything just yet based on the “one word” whispered to you at a cocktail party.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Solar I – The energy of the future (and always will be?)

Solar II – Tracking the rise of battery storage to see the future

Post read (63) times.