See related post In Praise of SIGTARP Part I here

See related post In Praise of SIGTARP Part I here

We are now at the four year mark on the deepest part of the Great Credit Crunch and Great Recession, so I’m moved to ask:

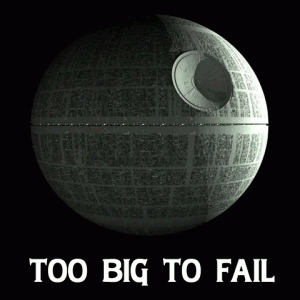

When it comes to avoiding the next financial blowup and bailout we need to ask “Are our bank protections better off now than they were four years ago?”

A Congressionally-mandated investigative entity, SIGTARP[1], AKA the Norse God of Financial Accountability, does not think so.

We know the United States government leaped into bailout frenzy throughout 2008, attempting virtually every permutation of intervention to keep the country’s largest financial institutions – and by extension – the world economy – from complete collapse. The US government used mergers, direct investments, shotgun marriages, bankruptcy, receivership, loan guarantees, voluntary asset sales, forced asset sales – the whole toolkit.

While the bailout process could best be described as ad-hoc, we hope that the delicate unwinding of the government safety net for Too Big to Fail institutions will be more thoughtful, and less chaotic.

We hope, however, in vain.

According to the SIGTARP report the bank’s exit from government protection has been quite ad-hoc as well. Worse, we[2] let weak TBTF banks pay back public funds before they were really steady on their feet with enough capital. The same banks – Citibank, Bank of America, Wells Fargo – remain weakly capitalized. This matters a whole lot because taxpayers continue to silently subsidize the safety net for TBTF banks.

SIGTARP’s report on repayments by the TBTF banks raises and answers key questions, such as

- Why did banks want to repay TARP money so quickly, before they were fully ‘ready’ to access private markets for their funding?

- How do we know the process was ad-hoc and rushed?

The answer to question number one is simple. Bank executives said it was to remove the shame and stigma of continuing to receive public bailout funds from TARP. I think anyone who has spent time around finance executives, however, knows that shame could not possibly weigh as heavily on them as did the TARP restrictions on executive compensation. [3]

The answer to question number two forms the bulk of SIGTARPs report from September 29, 2011, and the details are fascinating.[4]

To get the full gist of the issue, we need some background first, which SIGTARP nicely provides.

The authority to directly invest in TBTF banks[5] via preferred shares came with a sensible proviso that banks could not repay TARP money for 3 years, but Congress reversed course a few months later in early 2009 with a new law[6] that allowed banks to repay the borrowed capital more quickly. Although TARP money came from Treasury, the Federal Reserve Board headed up the regulatory team[7] charged with setting criteria for repayment.

Nine reasonably well-capitalized banks[8] repaid TARP funds in June 2009, while another eight – including 3 of the 4 largest banks in the country(Citigroup, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo) – failed a bank stress test. Among the criteria developed then for the weaker banks was a requirement that they raise a significant amount of TARP repayment funds – specifically 50% of the cash required for repayment — through common stock issuance.[9]

When push came to shove, however, we learn from SIGTARP’s report that regulators stretched, pulled, waived, and disagreed with one another about whether to make banks comply with the rules they had just put in place. Treasury’s rush to encourage repayment, it turns out, trumped the regulatory need for strong banks. And if you suspect large banks get better treatment than small banks, here’s your evidence.

Bank of America, for example, raised capital partly through preferred shares issuance, a less regulated type of capital. Citigroup, as well, fell short of its required 50% issuance of common stock. Wells Fargo attempted multiple times to wriggle out of the need for a fully dilutive equity issuance but ultimately raised the required amount at the end of 2009. Regulators, nevertheless, signed off on all three banks’ 2009 repayment plans, waiving their own requirements mere months after setting them.

FDIC’s then Chairman Sheila Bair, however, stands out as a vocal critic of the regulatory cave-in to the combined Treasury and bank-executive pressure.

Treasury, FRB and OCC officials apparently claimed that private markets were too weak to support the admittedly massive equity issuance needed for the banks. Paradoxically, at the same time Treasury, FRB and OCC implied the direct opposite, that banks were strong enough to pay back public funds.

As FDIC Chief Sheila Bair points out,

“The argument [FRB and OCC] used against us – which frustrated me to no end – is that [Bank of America] can’t use the 2-for-1[10] because they’re not strong enough to raise 2-for-1. That just mystified me. The point was if they’re not strong enough, they shouldn’t have been exiting TARP.”

Sheila Bair called out the impossible double-speak coming from Treasury, the Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

It makes sense to me that you can’t be both too weak for private capital markets but plenty strong enough to leave public protection. Regulators blew it by letting the banks out of TARP too early.

As a result of the rush to re-privatize we missed the chance to control, from a regulatory standpoint, the destiny of TBTF institutions and our public exposure to the next big crisis.

SIGTARP’s September 2011 report has a ‘remains to be seen’ conclusion on whether banks are now strong enough to absorb future financial shocks. That’s a pretty interesting negative-report from within the government, significantly doubting whether regulators have properly done their job.

Also, there’s this, from SIGTARP:

“Unless and until such institutions, either on their own accord or through regulatory pressure or

requirements, are restructured, simplified, and maintain adequate capital to absorb

their own losses, they will pose a grave threat to the entire financial system.”

That’s a compelling and scary argument right now, with Bank of America stock down 50% and Citigroup down 30% from when they repaid TARP in November 2009.

Also, please see In Praise of SIGTARP Part I here

SIGTARP Part III- The Citigroup Bailout

SIGTARP Part IV – Which Small Banks are Going Under Next?

and SIGTARP Part V – The AIG Bailout

[1] AKA Special Inspector General of the Troubled Asset Relief Fund.

[2] And by “we” I really mean primarily the US Treasury Department.

[3] When explaining bank executive behavior, always assume personal compensation comes first, until proven otherwise. It’s just a rule I follow and it’s never steered me wrong. Bankers feeling shame at receiving public funding to save their bacon? Please don’t insult me.

[4] All of this is assuming you find financial regulatory reviews fun reading, as I do.

[5] Through the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 of October 2008

[6] Through the American Recovery and Investment Act of February 2009

[7] Generally the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)

[8] GS, MS, JPM, US Bancorp, Capital One, Amex, BB&T, BONY/Mellon, State Street

[9] Regulators like common stock issuance because it improves a bank’s ability to absorb future losses, ie. it’s ‘capital ratios.” Bank executives dislike stock issuance because it dilutes value for shareholders, including themselves.

[10] “2-for1” is the regulatory short-hand language to indicate that 50% of TARP repayment money must be raised as new common equity

Post read (6987) times.