When we talk about making good financial decisions over a lifetime, we often assume they flow from a combination of willpower and knowledge. Essentially, as long as our brain is screwed on tightly, we can do this. Good decisions follow.

One of the most intriguing branches of behavioral finance – described in the 2013 book Scarcity: The New Science of Having Less And How It Defines our Lives by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir – suggests that our brains face an unfair fight under certain conditions. Specifically, the lack of something – scarcity – makes us unable – cognitively – to make the right decisions to overcome our lack in the long run.

The authors study more than just financial scarcity: Starvation, busyness, and loneliness are all experiences of scarcity of important resources – food, time, or personal connection.

The first effect of scarcity, they argue, can actually be positive. Scarcity focuses the mind. Newspaper writers know the value of a tight deadline for completing work. Low-income contestants on The Price is Right gameshow have a huge advantage over wealthy people who haven’t ever needed to focus on such forgettable matters as the exact retail price of Gold Bond Medicated Powder. The last stick of gum in the pack sure seems unusually delicious and valuable to my kids, who never, ever, share it with Daddy.

But that increased mental focus or heightened value for a scarce resource comes at a mental cost. By tunneling our vision on some things, we lose the ability to deal rationally with others.

In study after study, the authors show, we all tend to exhibit this behavior. In the realm of finance, researchers simulate poverty or abundance and find that our brains become either impaired or sharpened – for better and worse – in both instantaneous and long-lasting ways.

The effect works the same on the rich and the poor. Meaning, our brains react automatically to conditions of scarcity – even if it is artificially-induced scarcity – in a lab. We all perform worse on IQ-type tests when made to feel poor. We all seek to squander resources, or hoard resources, in predictable ways when faced with abundance or scarcity.

One mechanism by which scarcity leads to a cycle of poverty looks like this. A lack of money increases our mental focus on immediate savings or cashflow, but greatly reduces our ability to think outside of the immediate need. Good personal finance choices, unfortunately, often require us to rationally decide between complex choices with effects that will play out over months, years, and decades.

What does that cause? It means someone becomes less able to plan for one month from now (savings) or 25 years from now (retirement investing) or for an unexpected and costly illness (health-insurance). The same mind-focus on stretching a few dollars effectively from today to tomorrow will prevent our brains from seeing outside of our immediate challenge.

The authors point out that sometimes what looks like poor financial choices from the outside is actually both highly rational for someone maximizing scarce resources, as well as an unconscious response by our brains under conditions of scarcity.

Throughout the book I found myself reflecting on all the ways big and small, short and long, I’ve felt these effects. A multi-hour calorie-deficit at 7pm makes for a different type of thought-process for me.1 The unpleasant brain fuzziness after learning about a larger-than-anticipated tax bill. Attention-deficit when receiving pleasant, or unpleasant, texts on my phone while hurtling down the highway in my car at 70 miles-per-hour. A kind of perseverative neediness can take over my brain when I’m lonely.2

Of course, poverty is not the only thing weighing on a poor person’s mind. Culture, past-experiences, and individual personalities could all play even larger roles in what happens to someone in poverty. Scarcity of money is only one of many factors.

But, the authors argue, scarcity tends to affect our minds in a way that reinforces poverty.

As Americans we enjoy the myth that if we all just could yank aggressively on our bootstraps, we will rise above our inherited place in society.

Understanding the scarcity mindset, however, tends to undermine this myth. It is literally harder for a brain in poverty to focus on the steps necessary to cure the poverty. Our brain becomes our own enemy in this aggressive bootstrap-yanking project.

It’s not hard to extend the logic of these economists’ book to contemporary policies.

Andrew Yang’s quixotic campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination has only about 4 minutes left to it, but he has brought one lasting policy idea to the fore of American politics: Universal Basic Income, as either a supplement or as a replacement for existing welfare policies. It’s an idea I personally think should be more seriously debated, and deserves as much attention from the traditional Right as it does from the traditional Left of the political divide.

Maybe, the logic goes, if we reduced the tunnel-vision of poverty through a small basic income, recipients could focus on longer-term steps, like job-training or eliminating their pay-day loan debts.

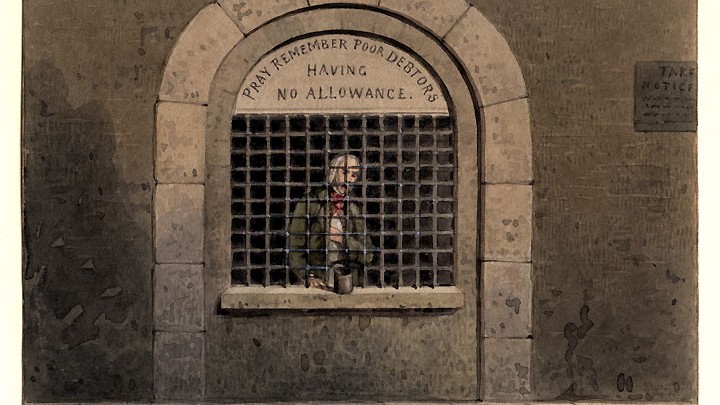

In the light of the Scarcity book, a move in the beginning of December by the federal government to restrict access to food stamps with a more restrictive work requirement doesn’t seem to take into account the work of Mullainathan and Shafir.

Compounding the scarcity of poverty with additional food scarcity seems not just cruel but ignorant of brain science. It’s a kind of 19th Century mindset reminiscent of debtors’ prisons. I think Mullainathan and Shafir would ask us to understand the effect of this type of thing on our brains better, if the goal is to break the cycle of poverty.

Behavioral finance research like in this book continues to take us down roads into the complexity of the human mind. We need continuous reminders of how un-simple the issues really are.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Universal Basic Income – That Right Wing Idea

Cash Rather Than Good Intentions

Post read (571) times.