Dear Michael,

My interest, as a long-term investor, is in what you have to say about small cap value vs growth funds and value vs growth investments in general. Don’t get me started on emerging markets and international funds – I’ve watched them for many years, and just don’t get the point. I believe in sticking close to home, especially with many larger US companies already involved in foreign countries’ economies. Anyways, keep the individual investor articles coming; they’re my favorite.

Dave M., San Antonio, TX

Dear Dave,

Thanks for your questions and comments, which give me a chance to get nerdy on asset allocation, finance theory, and investing practice.

First, some definitions. Value usually means “cheap” on some investment metric. You would expect to earn money through the steady continuity or recovery of the business. These often pay dividends which make up the majority of long-term returns.

By contrast, growth usually means the company isn’t done innovating within its industry, but may not pay substantial dividends as it strives for growth. Growth companies offer price appreciation as the driver of long-term returns. Value is more “fundamental” investing and growth is more “story” investing. Both are valid.

Small cap these days usually means public companies worth up to $2 billion or a little larger. Large cap usually means $10 billion or more, but ranges all the way up to trillion dollar+ companies. Mid cap means, you guessed it, in between $2 and $10 billion.

As an adherent to the efficient markets hypothesis, my initial answer to your question is that both growth and value are fine, all capitalization ranges are fine, and further that probably none is permanently better than the other. For multiple years in a row you could expect one style or capitalization range to outshine the other, only for that outperformance to be reversed in a subsequent decade.

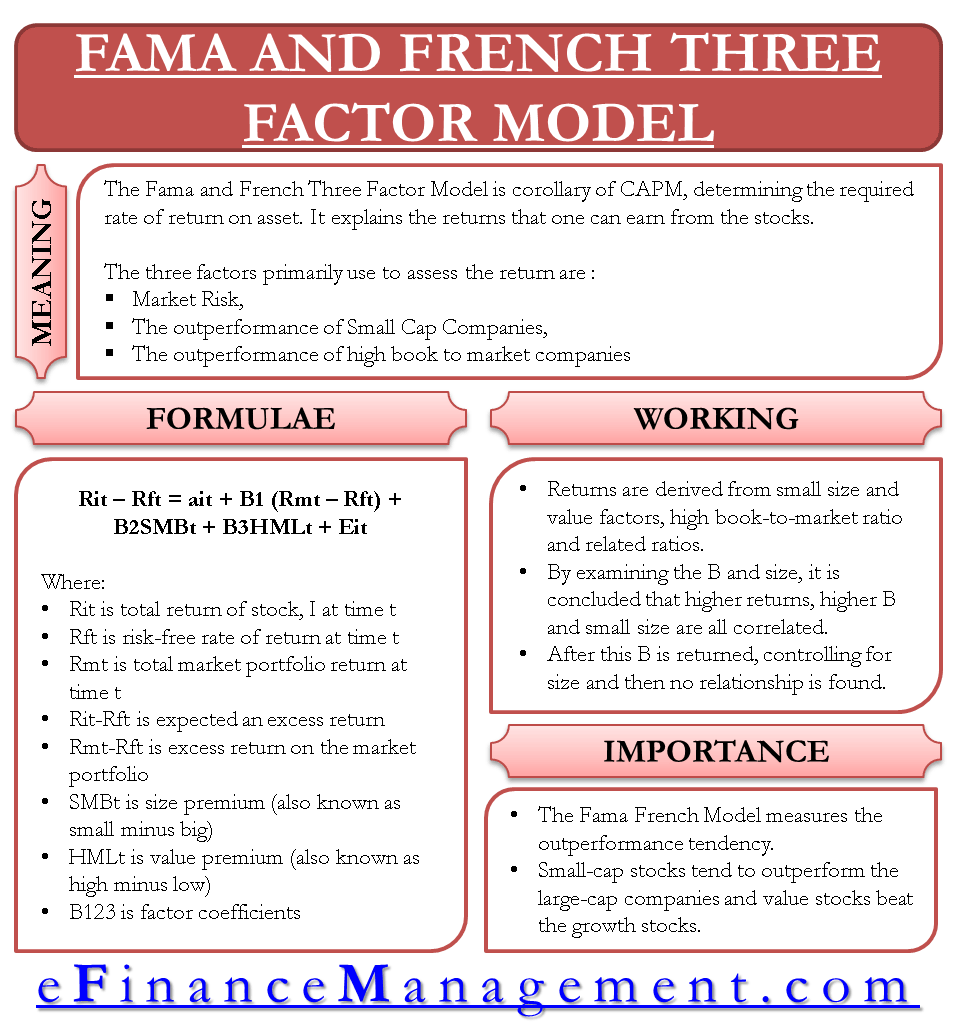

Beginning In the 1970s and continuing through the 2000s, finance theorists Eugene Fama and Kenneth French studied whether certain sectors consistently outperformed others. The short answer to their decades of research: Value stocks and small cap stocks seemed to offer higher returns in their analysis, based on data going back to 1928.

There are some intuitive reasons to think small cap and value investing might have advantages over other parts of the stock market.

Small companies’ shares may be inherently more volatile. Since investors often don’t like volatility, it makes sense that less investor capital would be allocated to volatile assets. That relative scarcity of capital would then raise returns for those brave souls who don’t mind volatility as much. In finance terms, efficient markets should still allow for a greater absolute return to higher volatility assets, as a compensation for the volatility. This could explain a persistent higher return for small caps when compared to large caps over the long run.

A similar theory could apply to value stocks versus growth stocks. Sometimes a value stock is relatively cheap because the CEO used bad words on social media or because the company sells known cancer-causing products like tobacco. Some investors don’t like bad words or cancer, so they don’t invest in those companies. That leaves a potential higher return for less squeamish investors. Like small cap investing, aversion by some investors might lead to persistent outperformance of value stocks for investors with less aversion.

So now you know which categories might outperform over the long run according to respectable finance theory. But also, they might not anymore? The confounding problem that keeps finance nerds awake at night is this: What is the time horizon measured? And do we still think that what Fama and French found holds true?

Also, if investors knew the results of Fama and French’s research (few individual investors know it, many professional investors know it, while all academics know it) wouldn’t they then favor value and small cap stocks, and the historical advantage would disappear due to investors’ interest in these sectors? The higher returns from any given sector (value versus growth, small versus large) seems, to me, logically ephemeral. Even so, I’m acknowledging ephemera may last for years or decades.

Large caps for example have absolutely crushed small caps over the last decade, and in particular the last few years. In fact, large growth stocks – currently dubbed the “magnificent seven” by the financial infotainment industrial complex – have been the place to be for a few years now. So again, make of that what you will.

The important thing, at the end of the day, is that if you can smoothly name-drop “Fama and French” and use the phrases “Efficient Markets Hypothesis” and “Capital Asset Pricing Model” in certain investment circles, people’s regard for you will skyrocket. “There goes a super-smart investor,” they’ll say, shaking their head with wonder in their eyes, as you saunter past.

And as for actually investing, maybe just try to own some of each category? Good luck!

To return to your international/emerging markets investing commentary and questions, we disagree.

As an “efficient markets hypothesis” advocate, the optimal non-US investment exposure should take into account – and roughly reflect – the weight of the US stock market versus global stock markets. Since US stocks are roughly 43 percent of global stocks, that’s the right place to begin – in theory – on how much of your investment portfolio should be in US stocks. For a fully-developed explanation of this specific idea, I highly recommend Lars Kroijer’s excellent Investing Demystified.

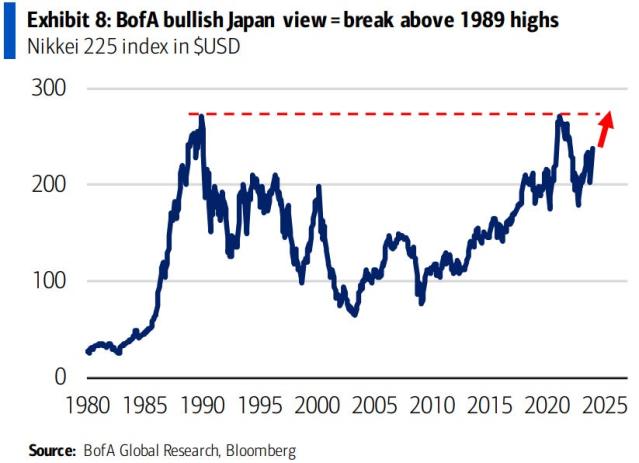

Further supporting Kroijer’s argument is the diversification problem that US investors typically have US-only real estate and US-only incomes and US dollar-denominated assets, so a US-heavy investment portfolio kind of stacks their correlation risks. Sophisticated citizens of other countries with substantial investments would never dream of investing only in their domestic stock market, domestic real estate, in their domestic currency, with their in-country domestic incomes. They are much more likely to seek to geographically diversify their financial risk exposures. History has borne out their very good reasons for doing this. A Japanese investor who bought their domestic Nikkei index in 1990 would still not have reached break-even levels, 34 years later. You don’t want to be that kind of undiversified investor. Even if you also believe deeply in American exceptionalism, which many of us do.

Now, in practice, I’ve never met a retail US investor with such a low US stock market exposure as 43 percent. And while I’ve told you my theoretical starting point, my wife and my retirement accounts are a combined 77 percent in US stocks. You also make a fine point that large multinationals in the US will have substantial non-domestic exposure. So you get some international exposure mostly via large-cap investing, but without having to take non-US regulatory, tax, and geopolitical risks.

Still, we have emerging market and developed country index funds in our retirement accounts. Maybe the best way to remain open to the idea of international diversification is that the next world-beating company just might come out of Brazil or India or South Korea or Belgium or South Africa. The top tech companies in the world won’t come from Silicon Valley always and forever, even if they did for the last 30 years. So I believe it’s worth having some future exposure to the next “Google from Bangladesh.”

Finally, my own retirement portfolio consists of just three positions, each 100 percent equity index mutual funds, in roughly ⅓ proportions: One international fund, one small-cap fund, and one high yield dividend-value fund. So while I’m somewhat skeptical about the Fama and French theory, I totally follow their lead anyway. It’s as good a plan as any.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Book Review: Investing Demystified by Lars Kroijer

Guest Post: Lars Kroijer on investing Agnosticism

Interview: Lars Kroijer Part I

Interview: Lars Kroijer Part II

Don’t Forget International Stocks

As an Ex-Banker – Mutual Fund Investing

Post read (94) times.