Slavery reparations are having a moment.

Barack Obama, America’s first Black President, never supported the idea, but the Democratic Party primary candidates for President in 2020 see things differently.

HUD Secretary and former San Antonio Mayor Julian Castro said as president he would set up a task force to look into reparations.

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren is on board even more forcefully, saying we must “confront the dark history of slavery and government-sanctioned discrimination.”

California Senator Kamala Harris answered questions regarding reparations positively, by referencing her anti-poverty proposals, although she did not explicitly link her proposals to race-qualifications.

Like Harris, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker has also tried to thread the needle, with his campaign linking his anti-poverty program [LINK:] to a “kind of reparations,” but without a race-component to qualify.

The average US voter does not currently advocate for slavery reparations in 2019. Polls show opposition to reparations still in the 68 to 70 percent range.

Nevertheless, like Medicare for All, this will come up as a talking point during the Democratic primary debates this year, as the party grapples with how left it can be ahead of the general election.

So what is the case for reparations?

Most of us probably don’t know the following.

General William Sherman set a precedent in January 1865 of distributing 400,000 acres in 40 acre plots, and then later the chance to rent a mule to work the land, from plantations captured at Sea Island, South Carolina to newly freed Black men, near the end of the Civil War. Sherman’s orders, at that moment in time, indicated a possible solution to the problem of compensating newly freed slaves, setting expectations for post-Civil War reparations. Even after President Andrew Johnson reversed Sherman’s orders following Lincoln’s assassination, “40 acres and a mule” became a symbolic request for the Federal government to make good its unfulfilled promise to former slaves.

The federal government’s financial policies toward Blacks did not improve over the next 100 years, as explained in the excellent 2017 book The Color Of Money: Black Banks And the Racial Wealth Gap by Mehrsa Baradaran.

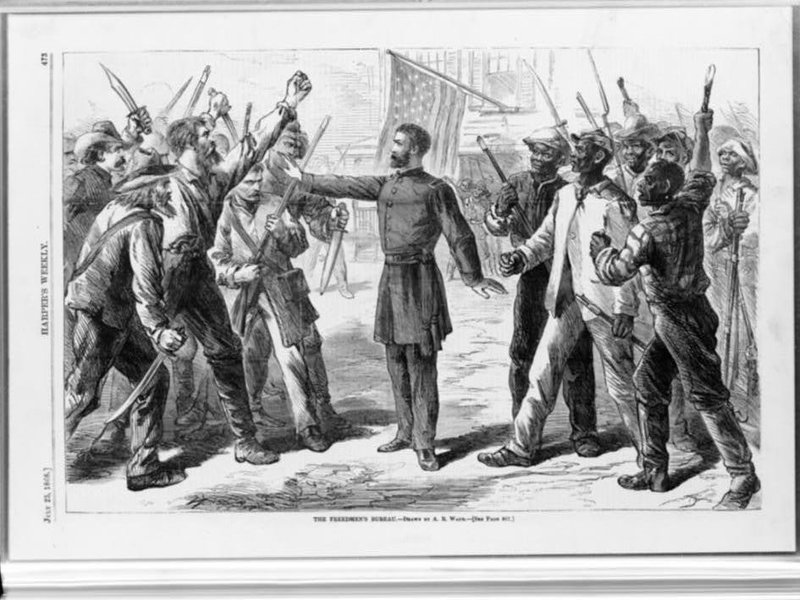

The federal government created the Freedman’s Bank in 1865 with Lincoln’s signature and Congressional approval. The Bank initially successfully encouraged thrift and banking until the (White) managers engaged in speculation and fraud that wiped out the bank, and with it about half the savings of all depositors. W.E.B Dubois would later say of the federally-chartered banking incident, “Not even ten additional years of slavery could have done so much to throttle the thrift of the freemen as the mismanagement and bankruptcy of the series of savings banks chartered by the Nation for their special aid.”

After 1934, when the Federal Housing Administration got into subsidizing mortgage loans to encourage wealth creation through homeownership, the federal government specifically set up rules that forbade private banks from lending to what it deemed dangerous neighborhoods. The purpose of the rules was to enforce high loan quality for the safety of the banking system and government guarantees. The effect of the rules, however, was to create a red line around Black and Brown neighborhoods, with households unable to obtain financing from any bank participating in the federal mortgage subsidies. This “redlining“– which continued as official FHA policy for the next three and a half decades but which caused financial reverberations that continue to this day – ensured that traditional Black neighborhoods languished in a vicious cycle of high interest rates, undercapitalization and disrepair, and a lack of asset appreciation.

White America has generally been blissfully ignorant of this history or the inter-generational effect it has on wealth inequality. The American Dream that White America cherishes and proudly proclaims sounds quite different to Black ears.

Do the American Dream clichés of hard work and bootstraps fully explain the fact that the median White household has ten times the wealth of the median Black household in 2016? Or is the origin of this inequality more complex? If the story is more mixed, do we as a society need to address the roots of wealth disparity?

I really don’t know.

And then there’s a practical question: what would reparations look like?

Moving beyond empathy, administering reparations could be a nightmare. Would people have to prove their slave ancestry to qualify for money? Do we have documentary and DNA records good enough to make accurate determinations? Is suffering under 20th Century Jim Crow enough, or is slavery the cutoff? Is being denied voting rights through early 1960s enough? What about more subtle, but still real, everyday racism in the present day? Open-ended questions about reparations are easier to produce than practical answers.

Reniqua Allen, the author of It Was All A Dream: A New Generation Confronts The Broken Promise To Black America wrote her book as a combination socioeconomic journalism and narrative about the struggles of Black Millennials, For her, the question of reparations has a monetary component, which she acknowledges would be incredibly complex to deliver. But a crucial idea of reparations, from her perspective, is acknowledging history.

“African Americans do believe in the American Dream. They’d like to believe in it. It’s frustrating to see it not happening. Largely people want security, and family, and what it represents.”

Even with this buy-in on the American Dream, however, she wants White Americans to understand the different narrative that Black Americans experience.

“But [reparations] I also think, it’s about acknowledgement, that there was a wrong, a major wrong, and it’s about seeing how those [wrong] actions reverberate to this day.”

As I listen to Reniqua Allen on reparations, I sense money may not be the main thing White America needs to offer here.

Allen and I shared a panel about inequality in America at the San Antonio Book Festival, April 6, 2019.

A version of this post appeared in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

Book Review: The Color of Money by Mehrsa Baradaran

Post read (482) times.